Principles

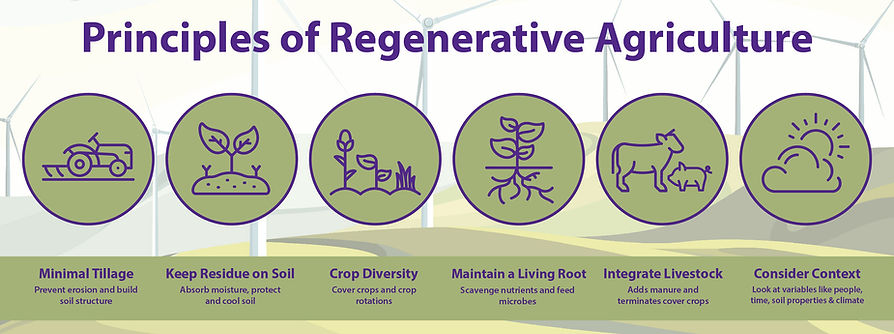

We prioritize regenerative agriculture's six key principles for their transformative potential in Kansas and beyond. By emphasizing crop diversity, reduced tillage, soil cover, living roots, integrated livestock, and context-specific practices, KSURA supports efforts to restore soil health, conserve water, and build resilient farming systems. These principles collectively improve soil structure, enhance water retention, increase biodiversity, and foster carbon sequestration, creating sustainable, profitable agricultural systems that also help mitigate climate change.

The Six Principles of Regenerative Agriculture

Fostering a sustainable future by embracing the principles of regenerative agriculture.

Regenerative agriculture is reshaping how we approach farming, focusing on restoring soil health, promoting biodiversity, and building climate resilience. These six principles serve as foundational guidelines for creating a sustainable, productive, and balanced agricultural ecosystem.

Six guiding principles for regenerative agriculture promote soil health, biodiversity, and sustainability in farming.

Minimal Tillage: Adopting No-Till or Reduced-Till Practices

No-till and reduced-till methods prevent soil erosion, protect soil structure, and prevent further soil degradation (Derpsch et al., 2010). These practices minimize soil disturbance, reduce evaporation, and improve water infiltration by encouraging the formation of soil macroaggregates. This improved soil structure enhances soil resilience to climate extremes such as drought and heavy rainfall. Additionally, no-till is a strategy to reduce atmospheric CO2 because it can protect existing soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks by reducing soil disturbance and increasing the mean residence time of SOC (Six et al., 2000; Six & Paustian, 2014).

Keep Residue on the Soil: Residue Management and Cover Crops

Maintaining soil cover is key to protecting farmland from erosion, reducing moisture loss, and suppressing weeds. Crop residues and cover crops provide this essential protection, shielding soil from the impact of wind, rain, and sun. Cover crop mixtures, particularly with legumes, can often lead to greater increases in SOC (Jian et al., 2020).

Crop Diversity: Crop Rotation and Prairie Buffer Strips

Historically, wheat-based monoculture systems that depended heavily on synthetic inputs to manage soil fertility and control pests were the norm in large swaths of Kansas. However, diversifying crop rotations or supplementing with beneficial microorganisms may be effective strategies for decreasing reliance on chemical inputs, improving the financial resilience of the production system, and increasing soil carbon stocks (McDaniel et al., 2014; Nicoloso & Rice, 2021; Arif et al., 2021). In a global meta-analysis, McDaniel et al. (2014) found that adding one or more crops in rotation to a monoculture system increased total carbon stocks by 3.6%. Additional diversity can be added to the system through perennial crops or prairie strips, which prevent erosion, reduce nutrient leaching into waterways, and support native pollinators (Schulte et al., 2017).

Maintain a Living Root: Incorporate Perennial Crops and Cover Crops

Roots produce exudates that serve as food for fungi and microbes, so the more often roots are in the ground, the more food there is for these tiny creatures, which are the engine of healthy soil. The presence of a living root also acts as an anchor for the soil, providing a major defense against wind and water erosion. Increasing perennials in rotations effectively improves soil health and reduces weed and pest pressure (King & Blesh, 2018). Perennial roots are deeper and more extensive. These

roots help to create soil structure, increase soil organic matter, improve soil moisture retention, and enhance microbial diversity, resilience, and fertility (Zhang et al., 2023).

Integrate Livestock: Crop-Livestock Systems and Grazing Management

Incorporating livestock into a cropping system can offer a range of regenerative benefits. When managed effectively, livestock grazing on annual crop residues and/or cover crops can enhance soil carbon storage and improve soil health. Practices such as rotational grazing, where grazing intensity and duration are managed based on climate, water availability, and soil type, can significantly increase soil carbon (Salton et al., 2014). Grazing livestock on cover crops provides an additional revenue stream (Peterson et al., 2020). Also, livestock manure can provide nutrients for crop production.

Consider Context: Tailoring Your Management to Your Agroecosystem

The final principle regenerative agriculture emphasizes is matching your practices to the unique conditions of your farming environment. Soil type, climate, and farm-specific goals guide the implementation of regenerative practices. This adaptability maximizes benefits while supporting social, economic, and environmental sustainability. The combined effects of regenerative practices work synergistically to confer the greatest benefits to the system (Bai et al., 2019). However, with so few established long-term regenerative agricultural experiments, comparatively assessing the outcome of many regenerative practices is difficult. In the absence of established experiments, recent observational studies have collaborated with dedicated producers to evaluate the impact of their regenerative management systems (e.g., LaCanne & Lundgren, 2018; Soto et al., 2021).

Citations

1. Arif, M., Ikramullah, Jan, T., Riaz, M., Akhtar, K., Ali, S., ... & Wang, H. (2021). Biochar and leguminous cover crops as an alternative to summer fallowing for soil organic carbon and nutrient management in the wheat-maize-wheat cropping system under semiarid climate. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 21(3), 1395-1407.

2. Bai, X., Huang, Y., Ren, W., Coyne, M., Jacinthe, P. A., Tao, B., ... & Matocha, C. (2019). Responses of soil carbon sequestration to climate‐smart agriculture practices: A meta‐analysis. Global change biology, 25(8), 2591-2606.

3. Derpsch, R., Friedrich, T., Kassam, A., & Li, H. (2010). Current status of adoption of no-till farming in the world and some of its main benefits. International journal of agricultural and biological engineering, 3(1), 1-25.

4. Jian, J., Du, X., Reiter, M. S., & Stewart, R. D. (2020). A meta-analysis of global cropland soil carbon changes due to cover cropping. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 143, 107735.

5. King, A. E., & Blesh, J. (2018). Crop rotations for increased soil carbon: perenniality as a guiding principle. Ecological applications, 28(1), 249-261.

6. LaCanne, C. E., & Lundgren, J. G. (2018). Regenerative agriculture: merging farming and natural resource conservation profitably. PeerJ, 6, e4428.

7. McDaniel, M. D., Tiemann, L. K., & Grandy, A. S. (2014). Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta‐analysis. Ecological Applications, 24(3), 560-570.

8. Nicoloso, R. S., & Rice, C. W. (2021). Intensification of no‐till agricultural systems: An opportunity for carbon sequestration. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 85(5), 1395-1409.

9. Peterson, C. A., Bell, L. W., Carvalho, P. C. D. F., & Gaudin, A. C. (2020). Resilience of an integrated crop–livestock system to climate change: a simulation analysis of cover crop grazing in southern Brazil. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 604099.

10. Salton, J. C., Mercante, F. M., Tomazi, M., Zanatta, J. A., Concenço, G., Silva, W. M., & Retore, M. (2014). Integrated crop-livestock system in tropical Brazil: Toward a sustainable production system. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 190, 70-79.

11. Six, J. Α. Ε. Τ., Elliott, E. T., & Paustian, K. (2000). Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: a mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 32(14), 2099-2103.

12. Six, J., & Paustian, K. (2014). Aggregate-associated soil organic matter as an ecosystem property and a measurement tool. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 68, A4-A9.

13. Soto, R. L., de Vente, J., & Padilla, M. C. (2021). Learning from farmers’ experiences with participatory monitoring and evaluation of regenerative agriculture based on visual soil assessment. Journal of Rural Studies, 88, 192-204.

14. Zhang, S., Huang, G., Zhang, Y., Lv, X., Wan, K., Liang, J., ... & Hu, F. (2023). Sustained productivity and agronomic potential of perennial rice. Nature Sustainability, 6(1), 28-38.